Medical Device Encryption for Non-Engineers

A practical guide to medical device encryption for QA and Regulatory professionals. Learn symmetric vs asymmetric encryption, key management, and quantum computing implications.

Summary

- Encryption transforms readable data (cleartext) into scrambled data (ciphertext) that only authorized parties can read. This is the foundation of medical device data protection.

- Keys are the secret, not algorithms. Encryption methods like AES are public. Security depends entirely on protecting the keys.

- Symmetric encryption is fast and suited for bulk data. Asymmetric encryption solves the key-sharing problem. Modern devices use both together in a hybrid approach.

- Key management is as critical as encryption itself. Generate, store, rotate, and retire keys properly, or the encryption becomes worthless.

- Quantum computing will break current asymmetric encryption. Devices shipping today should use AES-256 and plan for cryptographic migration.

What you'll learn: How medical device encryption protects data from sensor to cloud, and what QA/RA professionals need to know for design reviews and FDA submissions.

Introduction

Medical device encryption documentation can feel impenetrable. You encounter algorithms, key lengths, cipher modes, and terminology that seems designed to exclude anyone who isn't a cryptographer.

Here's the good news: encryption relies on just a handful of core concepts. Once you understand these fundamentals, you can participate confidently in any cybersecurity design review.

This guide explains medical device encryption using a Bluetooth glucose monitor as a practical example. You'll see exactly where encryption occurs, from the moment a reading leaves the sensor to when it arrives in the cloud. We'll cover the difference between cleartext and ciphertext, how encryption keys work, the distinction between symmetric and asymmetric encryption, why key management deserves more attention than it typically receives, and what quantum computing means for devices shipping today.

Whether you're reviewing cybersecurity documentation, preparing FDA submissions, or simply want to ask better questions in design reviews, this guide provides the foundation you need. For the full regulatory context, see our guide to FDA cybersecurity requirements for medical devices.

Why Medical Device Encryption Matters

Health data is extraordinarily valuable. Medical records sell for ten times the price of credit card numbers on the dark web. Medical devices transmit this sensitive data wirelessly over BLE, WiFi, and cellular networks, often in environments outside your control.

Without encryption, anyone nearby could intercept glucose readings as they travel from a monitor to a phone. This isn't a theoretical concern. It's exactly the attack model FDA expects manufacturers to address.

What encryption does: Encryption takes readable data (called cleartext) and mathematically transforms it into scrambled data (called ciphertext). Only someone possessing the correct key can reverse the transformation and recover the original data.

Here's a simple example:

| Cleartext (Readable) | Ciphertext (Scrambled) |

|---|---|

| Glucose: 125 mg/dL | 8x9Fj20aLp3bQz7y |

| Patient ID: 45678 | K0mN6wXvR1sT4uH |

| Timestamp: 14:30 | 7mQ2kL9pX5vN8aB |

FDA's 2025 cybersecurity guidance expects encryption for data at rest and data in transit. For most medical devices, encryption is not optional.

Keys Are the Secret

An encryption key is simply a piece of data, similar to a password but much longer and truly random. A key serves three functions:

- Locks data by encrypting cleartext into ciphertext

- Unlocks data by decrypting ciphertext back to cleartext

- Must remain secret because a compromised key renders the encryption worthless

Here's what often surprises people: the encryption algorithm itself is completely public. AES, RSA, ECC... anyone can read exactly how these algorithms work. The mathematics are published in academic papers. The implementations are open source. Security comes entirely from keeping the key secret.

Think of it like a lock on a door. Everyone understands how door locks work mechanically. That knowledge doesn't help you open a locked door without the key.

This is why key management matters so much. You could select the strongest algorithm available, but if your key leaks or gets stored improperly, you have no security at all.

For design reviews: Don't limit your questions to "what algorithm are you using?" Instead, ask "how are keys generated, stored, rotated, and destroyed?" Those questions address where encryption actually succeeds or fails.

Symmetric vs Asymmetric Encryption

There are two fundamental types of encryption, and each serves a different purpose.

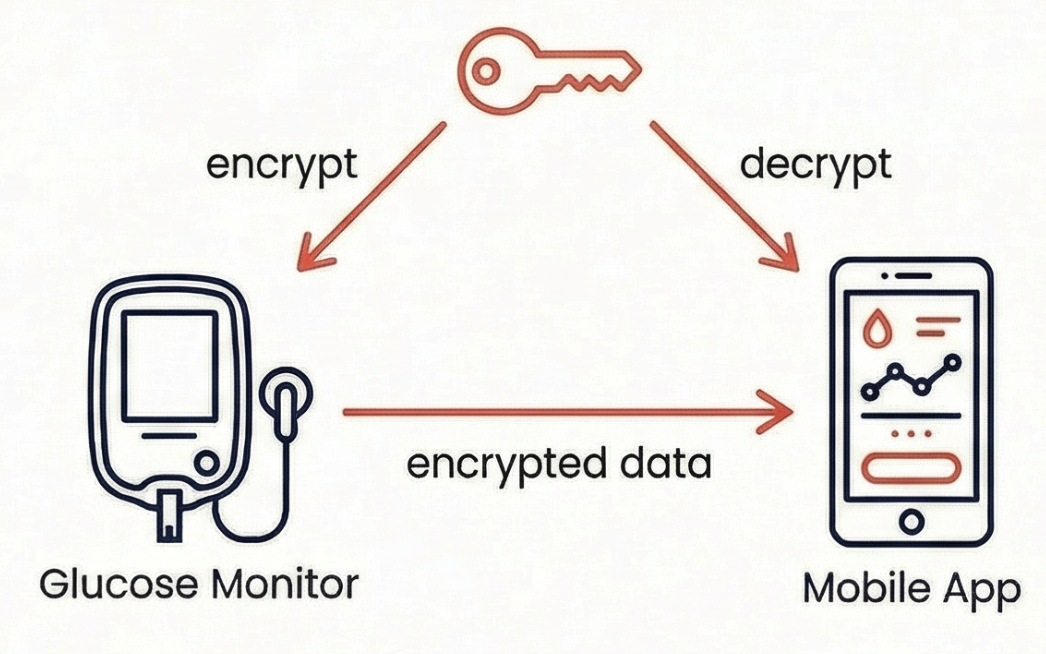

Symmetric Encryption: One Key Does Everything

In symmetric encryption, the same key both encrypts and decrypts. This approach is fast, efficient, and ideal for large amounts of data like continuous glucose readings.

The challenge with symmetric encryption is that both communicating parties need the same key. How do you share that key securely in the first place? If you transmit the key over the network, someone might intercept it. This creates a chicken-and-egg problem.

Current recommendations: AES-256 is the standard for new medical device encryption implementations. AES-128 remains mathematically secure against classical computers, but AES-256 is preferred for two reasons: it provides margin against future cryptanalytic advances, and it remains secure even after quantum computers weaken it (AES-256 drops to 128-bit equivalent security post-quantum, which is still acceptable; AES-128 would drop to 64-bit equivalent, which is not).

Algorithms to flag as outdated: If you encounter DES, 3DES (Triple DES), or any block cipher with keys shorter than 128 bits, flag it for replacement. These are legacy algorithms that no longer meet security requirements.

Medical device applications: Application-layer encryption on the device chip, encryption of stored data, and any scenario involving high-volume data transfer.

Asymmetric Encryption: The Key Pair

Asymmetric encryption uses two mathematically linked keys: a public key and a private key.

The public key encrypts data. Anyone can possess it. The private key decrypts data. Only the owner possesses it.

A useful analogy is a mailbox with a mail slot. Anyone can drop a letter through the slot (using the public key to encrypt), but only you have the key to open the mailbox and read the letters (using the private key to decrypt).

This approach solves the key-sharing problem elegantly. You can publish your public key openly, even posting it on a website or embedding it in a certificate. When someone wants to send you encrypted data, they encrypt it with your public key. Only your private key can decrypt it. The private key never needs to travel over any network.

The downside is speed. Asymmetric encryption is much slower than symmetric encryption, making it impractical for encrypting large amounts of data.

Current recommendations: For RSA, use a minimum of 2048-bit keys; 3072-bit or 4096-bit keys are recommended for new implementations and long-lived devices. Better yet, use Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) with P-256 or P-384 curves, which provides equivalent security with smaller keys and better performance.

Algorithms to flag as outdated: RSA with keys smaller than 2048 bits (RSA-1024 is broken), and any use of DSA.

Medical device applications: Initial device pairing, certificate validation, digital signatures, and authentication.

The Hybrid Approach: Best of Both

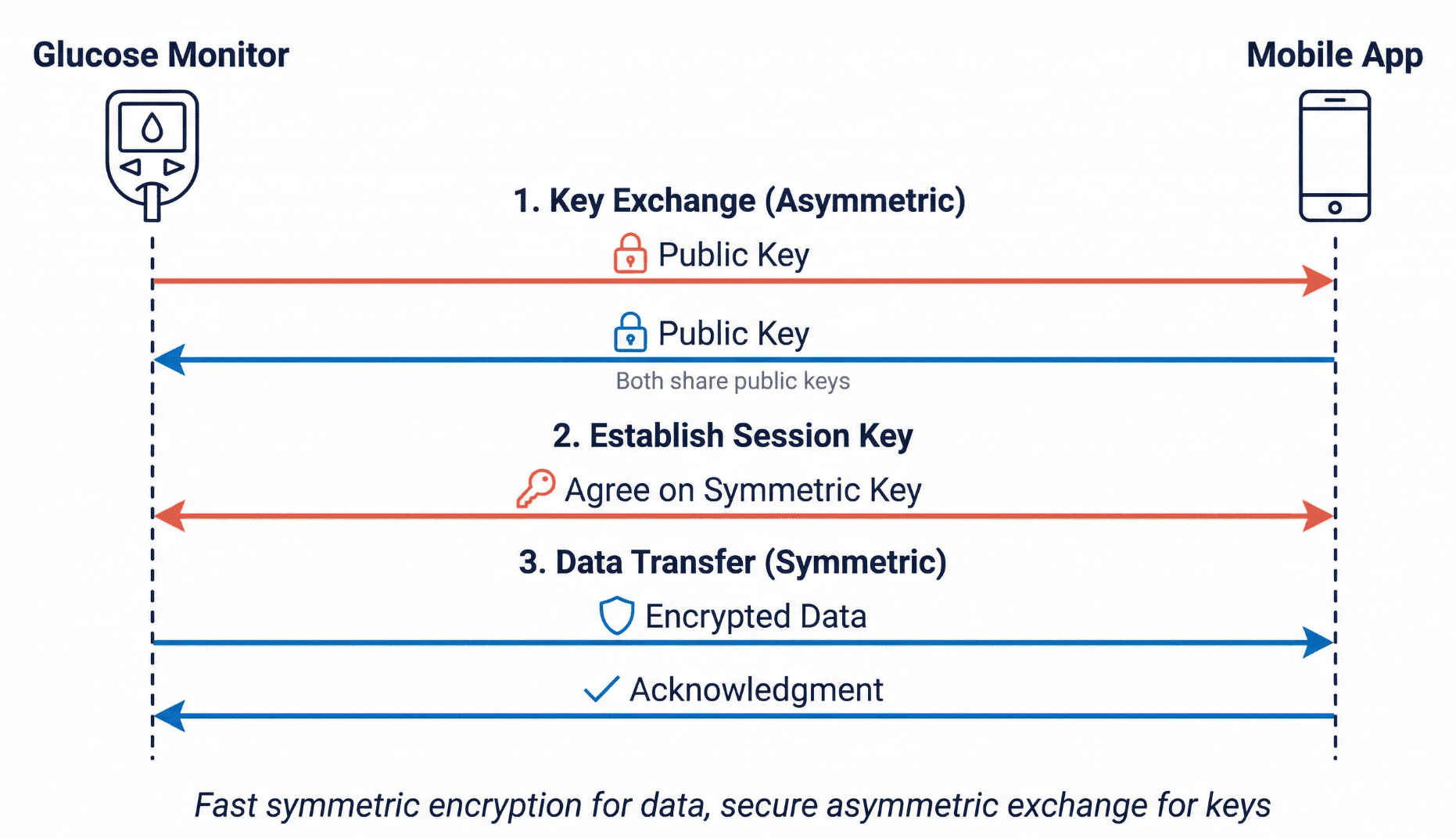

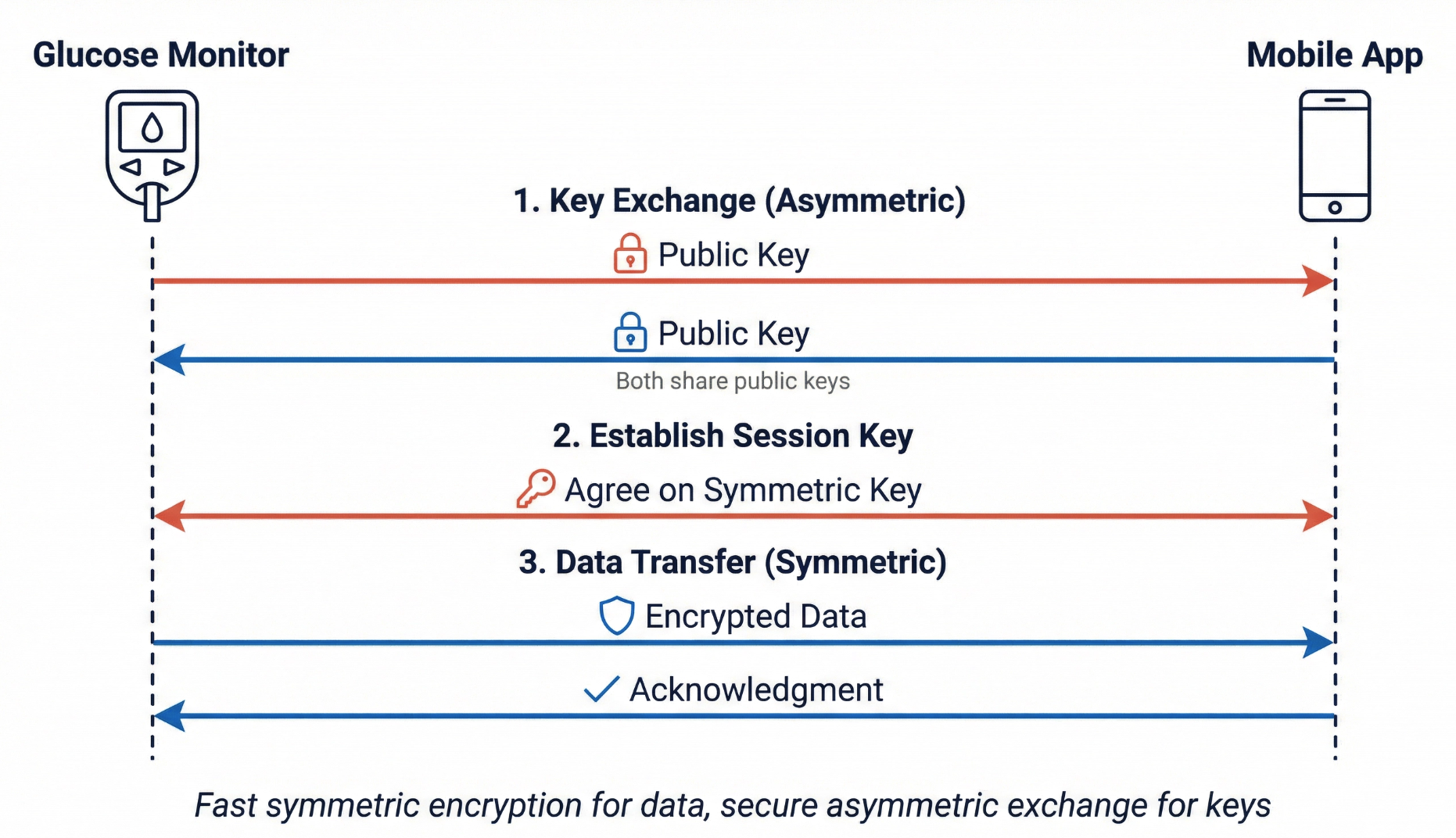

Modern systems combine both types of encryption. They use asymmetric encryption to securely exchange a symmetric key, then use that symmetric key for the actual data transfer. This provides asymmetric encryption's security for the key exchange and symmetric encryption's speed for everything else.

The process has three steps:

- Key exchange (asymmetric): The devices exchange public keys and verify each other's identity through certificates

- Session key establishment (asymmetric): The devices agree on a temporary symmetric key that will only be used for this session

- Data transfer (symmetric): The devices use the session key for fast encryption of actual glucose readings

This is exactly how TLS (Transport Layer Security) works. For medical devices, TLS 1.2 is the minimum acceptable version; TLS 1.3 is preferred. TLS 1.0 and 1.1 have known vulnerabilities and are deprecated. If you see these older versions in documentation, flag them for update.

BLE security note: Bluetooth Low Energy security depends heavily on the version and pairing mode. BLE 4.2 and later with LE Secure Connections provides strong security using Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) key exchange. Earlier versions (BLE 4.0/4.1) and legacy pairing modes like "Just Works" have significant weaknesses. When reviewing BLE implementations, ask specifically which pairing mode is used and whether LE Secure Connections is enabled.

For implementation details on these controls, see our guide on how to implement cybersecurity controls.

Key Management: The Four Pillars

Encryption is only as strong as the key management supporting it. Poor key management undermines even the strongest algorithms.

Generate

Keys must be generated from a source of true randomness, called entropy. This is one of the most common failure points in real-world cryptographic systems. If the random number generator is predictable, weak, or improperly seeded, the resulting keys may be guessable.

Hardware random number generators (HRNGs) are the standard for medical devices. These derive randomness from physical processes like thermal noise or radioactive decay. Software-based pseudo-random number generators (PRNGs) can be acceptable if properly seeded from hardware entropy, but they've been the source of numerous security failures when implemented incorrectly.

The secure chip in a glucose monitor should generate a unique cryptographic key during manufacturing using a hardware entropy source. The quality of that randomness determines whether an attacker could ever guess or brute-force the key.

Questions to ask: Where does the entropy come from? Has the random number generator been validated? Are there any conditions (like first boot or low-power states) where entropy might be insufficient?

Store

Private keys require protection. They should never exist in unencrypted form outside of hardened security environments.

Secure enclaves like ARM TrustZone, Apple Secure Enclave, and similar technologies isolate keys in dedicated hardware on the device itself. Even if an attacker compromises the main processor and operating system, the enclave continues to protect the keys.

Hardware Security Modules (HSMs) handle keys in manufacturing facilities and backend servers. These are tamper-resistant devices designed specifically for cryptographic operations. HSMs are certified to standards like FIPS 140-2 or FIPS 140-3, which provide assurance about their security properties.

Keys stored in cleartext in a configuration file, database, or application code represent a serious security finding.

Rotate

Keys should be replaced periodically. Rotation limits the damage if a key is ever compromised and reduces the amount of data encrypted under any single key.

Session keys are discarded after each connection. The symmetric key that your glucose monitor and phone agree on for today's sync will be gone tomorrow. Each new session generates a new key. This means that even if an attacker recovers one session key, they can only decrypt that single session's data.

Long-term keys rotate on a schedule determined by risk assessment. Device identity keys might rotate annually. Server certificates typically expire every one to two years. Certificate expiration is enforced by the infrastructure, so expired certificates will cause connection failures.

Retire

Keys must be destroyed properly when they're no longer needed.

When you unpair a device from your phone, both devices should erase the shared key. When you decommission a server, the HSM should be wiped. When a device returns for service, patient-specific keys should be cleared.

Improper retirement creates risk that old keys might resurface. If someone recovers a backup containing old keys, they could decrypt historical data.

For design reviews: Ask about all four pillars. Weakness in any one of them undermines the entire encryption system. AAMI SW96:2023 includes requirements for cryptographic key management that align with these principles.

Defense in Depth: Layered Medical Device Encryption

Production medical devices don't rely on a single encryption layer. They stack multiple layers so that if one fails, others continue to protect the data.

The glucose monitor in our example uses four distinct layers:

1. BLE Pairing The initial connection is secured via asymmetric key exchange using LE Secure Connections (BLE 4.2+). The monitor and phone establish a shared secret that authenticates all future communication. This layer stops nearby attackers from connecting to the device or eavesdropping on the wireless link.

2. Application-Layer AES Glucose data is encrypted at the application layer before it leaves the monitor's chip, using AES-256. This means the data is protected regardless of what happens at the transport layer. Even if the BLE security were somehow bypassed, the glucose readings would still be encrypted.

3. TLS 1.3 for Cloud Sync When the phone uploads readings to the cloud, TLS 1.3 protects the connection. This uses the hybrid approach: an asymmetric handshake (using ECDHE for key exchange) followed by symmetric data transfer (using AES-256-GCM). Certificate validation ensures the phone is communicating with the legitimate server, not an imposter. Proper certificate validation includes checking the certificate chain, expiration dates, and revocation status.

4. Encryption at Rest Data stored on the phone and in the cloud database is encrypted using AES-256. If someone steals the phone or breaches the server's storage, they obtain only ciphertext. The encryption keys for data at rest are themselves protected by the device's secure enclave or the server's HSM.

Each layer addresses different threats. BLE pairing handles local wireless attacks. Application encryption protects against transport failures. TLS secures the internet connection. Encryption at rest handles physical theft and storage breaches.

This layered approach is called defense in depth. Never stake everything on a single control. For more on this architectural approach, see Cybersecurity Starts with Security Architecture.

The Quantum Computing Challenge

Current asymmetric encryption methods will not survive the arrival of large-scale quantum computers.

Quantum computers, when they become sufficiently powerful, will break RSA and ECC completely. These asymmetric algorithms rely on mathematical problems (factoring large numbers, computing discrete logarithms on elliptic curves) that quantum computers can solve exponentially faster than classical computers using Shor's algorithm. No amount of key length increase will help; the algorithms themselves become fundamentally broken.

Symmetric encryption like AES is also affected, but it survives with adequate key length. Grover's algorithm allows quantum computers to search key spaces quadratically faster, effectively halving the security level. AES-256 drops to 128-bit equivalent security, which remains secure. AES-128 would drop to 64-bit equivalent security, which is below acceptable thresholds. This is why AES-256 should be the default for any new medical device encryption implementation.

The timeline is closer than many assume. While large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computers don't exist yet, both government agencies (NSA, CISA) and industry analysts have issued guidance to begin migration planning now. The concern isn't just about when quantum computers arrive. Adversaries are executing "harvest now, decrypt later" attacks today: collecting encrypted data and storing it until quantum decryption becomes possible. For health data with decades-long sensitivity and devices with 10-15 year lifecycles, the effective deadline is now.

Post-quantum cryptography standards are finalized. NIST published the first post-quantum cryptographic standards in 2024:

- ML-KEM (based on CRYSTALS-Kyber) for key encapsulation/exchange

- ML-DSA (based on CRYSTALS-Dilithium) for digital signatures

- SLH-DSA (based on SPHINCS+) for hash-based signatures

These algorithms resist all known quantum attacks. Major technology vendors are beginning integration, and regulatory bodies are watching adoption closely.

What this means for your submissions:

- Document all cryptographic algorithms your device uses, including key sizes

- Use AES-256 for symmetric encryption in new designs

- Consider your device's expected lifecycle relative to the quantum timeline

- Plan for cryptographic updates as part of post-market activities

- Design for crypto agility: the ability to update cryptographic algorithms through software/firmware updates without hardware changes or complete system redesign

FDA's 2025 guidance emphasizes ongoing risk management that addresses emerging threats. Quantum computing is an emerging threat that belongs in your threat model and should inform your cryptographic architecture decisions.

Key Provisioning in Manufacturing

Key provisioning often receives little attention in security training, but it matters enormously for quality assurance.

Every device needs a unique cryptographic identity. This requires injecting keys during manufacturing, a process that demands the same rigor as any other critical manufacturing step.

How key provisioning typically works: An HSM (certified to FIPS 140-2 Level 3 or higher) in a secured manufacturing environment generates keys using its internal hardware random number generator. The HSM loads keys onto each device through a secure channel and logs every operation. The HSM never exposes keys in cleartext outside its tamper-resistant boundary. The device's secure element receives and stores the key in its own protected memory.

Chain of custody documentation is essential. You need evidence that keys were generated properly, loaded only onto legitimate devices, and that no unauthorized copies exist.

Questions to ask about key provisioning:

- How are keys generated? The answer should involve an HSM with hardware entropy and FIPS certification.

- How are keys loaded onto devices? There should be a secure injection process with cryptographic protection.

- What happens if the manufacturing HSM fails? There should be documented backup and recovery procedures that maintain security.

- How are keys distributed to contract manufacturers? There should be secure key transport mechanisms, potentially involving key wrapping or split-knowledge procedures.

- Are key provisioning records auditable? There should be comprehensive logs with integrity protection and chain of custody documentation.

Key provisioning is a manufacturing process. It requires validation, documentation, and auditing just like any other process that affects device safety and effectiveness.

Quick Reference: What to Look For

When reviewing medical device encryption documentation, here's a quick reference for cryptographic elements:

Acceptable (current best practice):

- AES-256 for symmetric encryption

- RSA-3072 or RSA-4096 for asymmetric encryption

- ECC with P-256, P-384, or P-521 curves

- TLS 1.2 (minimum) or TLS 1.3 (preferred)

- SHA-256, SHA-384, or SHA-512 for hashing

- BLE 4.2+ with LE Secure Connections

Acceptable but monitor for updates:

- AES-128 (acceptable for non-quantum-sensitive applications with shorter data lifetimes)

- RSA-2048 (minimum acceptable; plan transition to 3072+)

Flag for replacement:

- DES, 3DES

- RSA-1024 or smaller

- MD5, SHA-1 for security purposes

- TLS 1.0, TLS 1.1, SSL

- BLE legacy pairing without LE Secure Connections

Conclusion

Medical device encryption protects data through mathematical transformation. However, the actual security depends on managing keys properly: generating them with true hardware randomness, storing them in hardened environments, rotating them on appropriate schedules, and retiring them completely when no longer needed.

You don't need to understand the underlying mathematics. You need to ask the right questions.

In your next design review, consider the following:

- Ask about all four key management pillars

- Verify that encryption covers both data at rest and data in transit

- Check algorithm choices against current recommendations (AES-256, TLS 1.2+, RSA-2048 minimum)

- Confirm that key provisioning is a validated manufacturing process

- Consider the device lifecycle and quantum preparedness

The algorithms are public knowledge. The standards are published. Security ultimately depends on implementation, and that's where QA and Regulatory oversight makes a meaningful difference.

References

-

FDA, "Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions," FDA Guidance, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/cybersecurity-medical-devices-quality-system-considerations-and-content-premarket-submissions

-

AAMI, "AAMI SW96:2023 - Medical device security: Security risk management for device manufacturers," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://array.aami.org/doi/book/10.2345/9781570208621

-

NIST, "Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography

-

NIST SP 800-57 Part 1 Rev. 5, "Recommendation for Key Management: Part 1 – General," 2020. [Online]. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-57-part-1/rev-5/final

This content is for educational purposes and represents interpretation of current regulatory guidance. Consult with qualified regulatory and security professionals for specific compliance decisions.